-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

-

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

Policing the District of Columbia prior to the creation of the

Metropolitan Police Department.

The District of Columbia, as we know it, was created on July 16, 1790, as a ten-mile square forming the nation’s new capital. Included in the new capital was a portion of Montgomery County, including the port city of Georgetown, portions of Prince George’s County, Maryland as well as the port city of Alexandria, Virginia, which was the county seat of Fairfax County, Virginia.

1791

On April 15, 1791, the first boundary stone of the district was laid at Jones’ Point [Alexandria, Virginia], which is still visible to this day. They named the district, “The Territory of Columbia” and decided that the federal city should be named, “The City of Washington.” Congress maintained the ultimate authority over the District, but it delegated limited local jurisdiction to the municipal government.

So, from its beginning, the District of Columbia operated as a unique entity in law enforcement. For the first ten years of its existence, a constable appointed by the Prince George’s Court served as the peace officer for the greater Washington area, while county constables appointed by Montgomery patrolled Georgetown and county constables appointed by the Circuit Court of Alexandria patrolled that section of the city.

The constables operated under the laws of either Maryland or Virginia, depending upon where they were in the city.

1800

The new federal district, known as the City of Washington, encompassed a population of 3,210 — 2,464 whites and 746 blacks. ( what was surprising me was the huge focus on the differences with the black and white community)

1802

On May 3, 1802, Congress passed the Acts of the Corporation of the City of Washington which provided a charter consisting of an elected twelve-member city council with two chambers and a mayor appointed by the President.

Among the powers of the new city was the authority to establish night watches or patrols, the imposition of fines and penalties recoverable as debts.

1803

On September 20, 1803, the position of Superintendent of Police was created and on Wednesday, September 28, 1803, Mayor Robert Brant [1802 – 1812], appointed John Willis as the Superintendent of Police with an annual salary of $200.

John Willis replaced the Constable who had been appointed by the Prince George’s County (Maryland) Court. The duties of the new Superintendent included notifying people to remove “all filth or other offensive substances, or nuisances or obstructions,” licensing slaughterhouses and kilns, visiting every part of the city at least once a month, and informing the magistrate of any violations of the law.

-Kenneth G. Alfers, Law and Order in the Capital City: A History of the Washington police, 1800-1886 (Washington: George Washington University, 1976.), p. 5.

1804

Less than a year later, on Monday, July 9, 1804, John Willis resigned, and Mayor Robert Brant appointed Cornelius Conningham as the Superintendent of Police.

[Some histories list Cornelius Cunningham as the first Superintendent of Police. Former Major and Superintendent of the Metropolitan Police Department, Richard Sylvester, in his book, District of Columbia Police – A Retrospect of the Police Organizations of the Cities of Washington and Georgetown and the District of Columbia, with Biographical Sketches, Illustrations, and Historic Cases, Gibson Bros., Printers and Bookbinders. 1894, names Cornelius Conningham as having been appointed Superintendent after the creation of the position.

The National Intelligencer reported the dates listed here for the appointments of John Willis and Cornelius Conningham.]

On October 13, 1804, the Council authorized the mayor to appoint up to four constables whose duty it would be “to give information of any violation of the acts of the council” to the proper officer and enforce their provisions.

–Sylvester, p.23

1805

On May 2, 1805, the office of the Superintendent of Police was abolished and was replaced with ‘the ‘High Constable’ of the city. The pay of the High Constable was lowered to $150 per year from that of the Superintendent.

Richard Spalding was appointed the High Constable and James B. Heard, Jacob Crawford, Clement Venable and Zephaniah Wade were appointed constables to the four wards of the city.

1807

On May 30, 1807, the Council assigned the duties of the High Constable to four City Commissioners, one for each ward, who were charged with the execution of all laws and the supervision of the constables.

The City Commissioner was also to determine the pay of the constable “over and above his legal fees and emoluments…for their vigilance and good conduct.” The extra compensation was not to be more than $200.

-Alfers, p. 6.

1808

On December 6, 1808, the Council passed an act creating two “Officers of Police” as well as dividing the city into two Districts.

The First District comprised “all parts of the city west of Fourth Street, West” and the Second District comprised “all parts of the city east of Fourth Street, West.”

The act provided that each Officer of Police was to be paid $100 semi-annuallyprovided the mayor and one branch of the City Council certified that he had “fully and satisfactorily discharged his duty.”

–Slyvester, p. 23; The National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser, 26 December 1808.

1811

On May 31, 1811, the Council disbanded the “Officers of Police” and placed their duties back onto the constables of the city.

1813

In 1813, The commissioners were Samuel McIntire, Walter Clarke, Henry Ingle,and John W. Brashears; and the constables, Nathan Moore, Brooke Edmonston,Walter Greenfield, and George Adams.

On March 30, 1813, the Council authorized the building of watch-houses in each of the wards of the city.

1814

The War of 1812 was devastating to the city. Amilitia had been raised and formed and went out to meet the British. Back in the Washington, there were fears of a slave uprising, and that the city, “stripped of troops lay exposed not only to rebellious blacks but to lawless whites ready to loot the city.”

Mayor James H. Blake requested that every able-bodied man exempt from military duty join Committees of Safety in each ward. – Alfers, p. 7.

The militia initially denied the British access to the city by destroying the bridges over the Anacostia River. The British then marched around the city and entered from Bladensburg, Maryland.

The militia erected barricades, but the British advanced into the city on August 24, 1814, burning many of the buildings in the city and then left the next night.

During the burning of Washington, the Constables were not present, all having been called up for military duty. One of the concerns after the burning of Washington was whether the seat of the government would remain in Washington.

Joseph G. Brown replaced Walter Greenfield as a constable.

1815

In February 1815 Congress acted and authorized funds for the rebuilding of the federal buildings in Washington.

The Constables returned to Washington and the city began to grow.

1817

In June 1817, Mayor Benjamin G. Orr [1817 – 1819] went to the City Council stating that the laws in the city were “not as defective as their execution is remiss and negligent.”

Lack of a suitable penitentiary or workhouse and inefficient enforcement of the laws created a situation in which “vice, in every odious form, roams the city unrestrained.”

Mayor Orr recommended doubling the number of Constables to eight. The Council responded by adding one additional Constable.

The City Council then instituted a financial incentive system to reduce crime.

The City Council increased the fees associated with various crimes, allowing the Constables to earn more money by taking individuals to workhouses.

-Alfers, p. 7.

1818

“On October 19,1818, a fee of fifty cents was allowed constables for each whipping of a slave, who had been adjudged guilty of violating an act of the corporation.

In this year a revision of the law was authorized and $200 was appropriated to John Law for the work.”

-Slyvester, p. 24.

Thomas Edmonston was appointed a constable for the second ward, and S. A. Childs was appointed as an additional constable.

1820

The 16th Congress in 1820 authorized a new charter for the city of Washington. The new reaffirmed the power of the corporation, “to establish night watches or patrols” and to regulate blacks, slaves or free, and other “disorderly” people.

The City Council then divided the city into six wards and fired all five Constables replacing them with “six discreet, temperate, and respectable housekeepers, one in each ward, to be called, “City Commissioners.”

The new police officers were to be paid $250 annually.

-Alfers, p. 7.

1821

The revised policing system of “City Commissioners” was a failure and Mayor Samuel N. Smallwood when he addressed the City Council concluded that the city “cannot boast” of”well-regulated vigorous police.” and recommended that the commissioner system of policing be abolished.

The policing system in the city was changed again and Mayor Smallwood was given the power to appoint a police constable to each of the six wards. The police constables assumed the police duties previously exercised by the commissioners, and they reported directly to the mayor. Pay for the police officers was $100 per year.

The constables were Wm. Serrin, John Waters, C. W. Boteler, J. W. Beck, Wm. Smith, and E. Bryan.

1825

During the 1825 Inauguration, the city Constables helped with the crowds at the Capitol but since the Inauguration went off without problems, their assistance was a mere footnote to the event.

1825 also saw a fire break out in the Congressional Library one night. This led to the creation of the city’s first regular night police force, although the two-man force was limited to guarding the Capitol.

This led to the first regular night police in the city, which consisted of two men guarding only the Capitol. Other areas of Washington continued to do without nightpatrols, a situation which becameincreasingly untenable as the city expanded.

-Alfers, p. 8.

1829

The 1829 Inauguration was unique in that it was the first time that the east portico was used. Andrew Jackson delivered a short crisp speech at the Capitol and was sworn in by Chief Justice John Marshall. Jackson had intended to skip the evening’s inaugural balls and wanted to keep the other ceremonies to a minimum, but things began to get out of hand.

“Thousands and thousands of people, without distinction of rank, collected in an immense mass round the Capitol,” Margaret Bayard Smith, a Washington socialite, wrote to a friend. Many were determined to follow Jackson to the White House along then-unpaved Pennsylvania Avenue.

Jobseekers wanted to button-hole him. Others wanted to join an open house that was to be held there.

“Country men, farmers, gentlemen, mounted and dismounted, boys, women and children, black and white, carriages, wagons all pursuing him to the President’s house,” Smith wrote.

It was what Representative James Hamilton Jr. called in a letter to Martin Van Buren a “Saturnalia.”

Members of Washington’s high society shuddered at what the Inauguration had descended into, and many wondered why “no police officers had been placed on duty.” The fact was that plans had been made.

The United States Marshal for the District of Columbia had requested the tiny force to assist him at the Capitol however the size and enthusiasm of the crowd had quickly overwhelmed the small force. From that time forward, the police in the District of Columbia took greater emphasis in dealing with Inauguration crowds.

1832

As the city of Washington grew, so did crime. In 1832, the City Council increased the size of the force from six men to ten.

On the 9th of August one additional constable each was authorized for the first and second wards and two for the third ward, and the mayor was directed to divide each ward correspondingly into districts. The compensation of constables was fixed at $50 per annum, with an allowance of $50 additional when they performed the dutyof commissioners.

The city commissioners at that time were Samuel Drury, C. L. Coltman, and Thomas Burch.

The constables were: First ward, Wm. Serrin, H. B. Robinson; second, David S. Waters, John B. Locke; third, R. R.Burr, Jilson Dove, Thos. J. Martin; fourth, John B. Speaks; fifth, Wm. Harrison; sixth,Wm. McGill. but that still wasn’t enough to keep pace. In the twenty-five years prior to the start of the Civil War, Washington nearly tripled in size.

-Slyvester, p. 26.

1833

The constables were Wm. Serrin, L. Ashton, D. S. Waters, John Waters, R. R. Burr, H. B. Robinson, John Stevenson, John Wells, and Matthew Jarboe.

The lock- ups or watch-houses authorized under the act of March 1813, were primitive structures, some of plank and others of logs, just as one or the other materialwas more convenient. They were ten or twelve feet square, and the only opening wasa door, in the upper part of which were the bars, through which the unfortunate inmates obtained light and air in limited quantities.

-Slyvester, p. 26.

1834

In 1834 the constabulary of Washington consisted of Wm. Serrin and L. Ashtonin the first ward; D. S. Waters and J. B. Locke in the second; R. R. Burr, H. В.Robertson, and T. J. Martin in the third; J. B. Speaks in the fourth; R. Speiden in the fifth, and W. McGill in the sixth.

-Slyvester, p. 26.

1836

In 1836, F. B. Poston and John Dewdney were Constables in the first ward, John Waters and J. W. Dexter, in the second, R. R. Burr, J. M. Wright, and Horatio R. Merryman, in the third ward, T. J. Barrett and R. Mills, in the fourth ward, John Magar in the fifth ward and Ignatius Howe in the sixth ward. W. H. McLean was a constable in the portion of the city known as the Island, afterwards designated the seventh ward. Besides performing their usual and a few extra duties, some of the constables were also clerks in the market and one was superintendent of the fish wharf, at the foot of Third Street, southeast.

-Slyvester, p. 26 & 27.

1842

In May 1842, the House Committee for the District of Columbia issued a report favoring the establishment of a night guard and Congress debated the topic before passing an Act on August 24, 1842, creating an Auxiliary Guard, “for the protection of the public and private property in the City of Washington.”

The Guard would be supervised by a Captain, who was appointed by the Mayor of Washington and the Captain would appoint a force of 15 men. The captain would be paid $1000 and five of the members of the Guard would earn $35 a month and the remaining ten members of the Guard would earn $30 a month.

John H. Goddard, a member of the Board of Alderman from the Third Ward was appointed Captain. He was armed with a revolver while the other 15 men of the Guard were armed with clubs. The uniform of the Guard was grey with brass buttons as well as a gray cap. On the brass buttons were the letters A. G., and their gray caps also bore the same letters. Instead of a whistle, the members of the Guard used a rattle. The Guard began operations on September 5, 1842, with half of the Guard working 9:00 P.M. to midnight and the other half of the Guard working until 4:00 A.M.

A dual operating police system was normal before the Civil War. New York did not unify their night and day police forces until 1844, and Boston consolidated their forces in 1854.

The Guard, although a small force, initially proved to be very capable, but the young force still had some hiccups.

In late 1842, President John Tyler was taking a walk on the grounds south of the Executive Mansion, when an intoxicated printer,who subsequently served as an auxiliary guardsman, threw a stone at the President. He was promptly arrested and taken before justice, but hardly had his name been entered and the charge made when a messenger from President Tyler appeared with a note expressing the President’s desire that if anyone was held for attacking him, he should be released at once. When questioned about the event, President Tyler stated that in political life he had found that sometimes zeal ran away with judgment and suggested that the matter be allowed to drop at that point.

-Slyvester, p. 28.

The headquarters of the guard was in what was known as the scale-house of Center Market, where calls were provided, andit was customary for the members to assemble there nightly, receive their instructions and proceed to their beats.

The uniform of the guard was grey with brass buttons on which were the letters A. G., the caps were also grayandwith the same A. G. lettering. In place of the baton, each officer carried a stick with an iron spearhead. The tool was originally intended to let the guardsmen pry open doors in case of fire or defensively when chasing thieves. Some of the officers became very proficient so that it made a formidable weapon either when used as a club or thrown as a javelin.

In terms of hierarchy, the guard didnot supersede the day police, but was, as its name implied, an auxiliary force. Instead of a whistle the officers used a rattle.

Captain Goddard’s first selections for the force were: Wm. G. Howison, EdwardI. Ellis, Thomas MacGill, Wm. Cox, S. Howard Taylor, John L. Fowler, Joseph Smith,Wm. B. Guy, Johnson Simonds, Thomas Sessford, John E. Little, Joseph Goodyear, Patrick Sweeney, Edgar H. Bates, and Solomon Hubbard.

-Slyvester, p. 29.

1846

The city council divided Washington into seven wards and raised the number of constables to 12.

1849

In 1849, Mayor William Seaton requested the City Council to reform the pay of the police in the city, moving away from a fee system to a more standard pay. The fee system enabled officers to supplement their salaries of $50 per year.

“It appears to me that it would be better for the corporation to create its own officers, allow them suitable salaries, require their time to be given all together to their police duties, and all fees arising from prosecution to be paid over to the Corporation.”

Many citizens complained that the police constables abused the fee system, “not among the rich and influential, but among the minorant’s, the degraded, the poor, the outcast, and the forsaken.”

Many of the 14 police constables held other jobs and at least eight constables served as constables for Washington County, a separate jurisdiction within the District of Columbia.

-Alfers, p. 15.

1851

On March 11, 1851, the City Council approved a police re-organizational plan. Seven police districts were created which mirrored the seven wards of the city. The mayor would appoint a “Chief of Police of the city of Washington” as well as with the advice and consent of the Board of Alderman. The reorganization called for two police officers for each District except for the Fourth District, where three officers would be appointed.

Outside employment was banned and officers were required to be on duty until the Auxiliary Guard came on duty.

The mayor also had the authority to have the police officers act as a night watch.

The constables were:

First Ward: John Dewdney and J. H. Craig

Second Ward: W. H. Barneclo and W. A.Boss

Third Ward: E.G. Handy and J. F. Wollard

Fourth Ward: Richard R. Burr, Wm.Martin and John Davis

Fifth Ward: W. A. Mulloy and James Lynch

Sixth Ward: John A.Willet and Josiah Adams

Seventh Ward: Issac Stoddert and U. B. Mitchell.- Slyvester, p. 30.

The Chief’s salary was doubled. Originally, the Chief’s compensation was set at $500, because the Chief could also serve as a Police magistrate and receive between $350 and $500 for that job.

Around the same time, Congress also doubled the Auxiliary guard. Fifteen of the Auxiliary Guard would be paid $500 a year, while the other fifteen members of the Auxiliary Guard would earn $420 per year. The members of the Auxiliary Guard were supplied badges which they wore on their hats. The badge was numbered and carried the inscription, “Auxiliary Guard”. The members of the Auxiliary Guard were provided with such weapons as the captain authorized.

Mayor Walter Lennox named John Goddard as the Chief of Police while Goddard also was Captain of the Auxiliary Guard.

The members of the Auxiliary Guard were:

Joseph Goodyear, Abraham Dixon, John Frere, Isaac Ross, William Hickerson, Joseph Williamson, Henry Thomas, Henry P. Queen, Thomas E. Williams, John Simonds, T. B. Cross, John E.Little, James Bean, Israel Wason, William M. Mockbee, Washington Lewis, George H. Grant, Francis W. Colclazier, Thomas A. Clements, Edward Thomas, Joseph W. King, John L. Fowler, lames Timms, Henry Horskamp, Thomas Gooden, Mason Piggott, Solomon Hubbard, Thomas W. Jones, J. W. Smith, and William Cox.

Some of the rules and regulations for the Auxiliary Guard were that they “shall at all times, under the direction ofthe Captain, render such aid as shall be found necessary to protect the public property in the city of Washington, and shall be fully empowered to execute all the dutiesimposed on the police officers of the Corporation, and thelaws of the land.”

-American Telegraph, July 2, 1851, p. 2.

“It shall be the duty of each member of the Guard toattend all fires which may occur in the daytime in theWard in which he resides; and It shall be the duty of those on service in any particular beat in which a fire may occur at night, to attend the same as also those onduty in the adjoining beats. Upon such an occasion they are required to use every exertion, not so much for the extinguishment of fires as for the preservation of orderand the protection of property.

-American Telegraph, July 2, 1851, p. 2.

No member will be allowed to be absent from the District without the permission of the Mayor or the Captain of the Guard.

-American Telegraph, July 2, 1851, p. 2.

1852

The double appointment of John Goddard as Chief of Police and Captain of the Auxiliary Guard was not without criticism.

Mayor Walter Lennox had argued that there was unity and efficiency in having a single individual controlling both forces.

Since the two jobs technically required Goddard to be working 24 hours a day, he recommended the creation of the position of Lieutenant of Police to assist Goddard.

Still, a lot of citizens were critical of Goddard for being paid $1000 to be the Captain of the Auxiliary Guard, while also earning $500 as Chief of Police.

Additionally, Goddard was also being paid to be a justice of the peace and a police magistrate.

On September 15, 1852, Horatio N. Steele, a former Deputy Marshal for the District of Columbia, was named the Chief of Police.

Congress on October 15, 1852, authorized the appointment of an officer to do duty at the B. and O. depot, then the only railway station in the city which was located at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and Second Streets, NW.

1853

Full time supervision for both forces was not a cure-all for the inefficiencies of either force. Complaints of vandalism, arson, prostitution, robbery, assault, and juvenile delinquency continued to worsen.

The allegations were that the Auxiliary Guardsmen “sit about the corners of streets either asleep or smoking cigars, instead of walking their rounds.”

-Alfers, p. 16.

James H. Birch replaced John Goddard as Captain of the Guard. New rules were instituted which stated that members of the Guard could be dismissed for engaging in any business besides their police work and/or for “a single instance of intoxication.”

Other attempts to improve Guard effectiveness included the requirement that members go on duty at 8:30 PM and leave their beats at daybreak.

Four of the Guards resigned rather than observe the new regulations; while others continued as they had before.

-Alfers, p. 16.

1854

In June, John Towers, supported by the Know-Nothings*, won the mayoral election. Towers began appointing his political friends to office “with full determination to put out of office naturalized citizens and members of the Roman Catholic Church.” Some of the political appointees were named to the city police forces, including the nomination of John Davis to replace Horatio Steele as Chief of Police.

* -The American Party, known as the Native American Party before 1855 and colloquially referred to as the Know Nothings, or the Know Nothing Party, was a political movement in the United States in the 1850s. Members of the movement were required to say “I know nothing” whenever they were asked about its specifics by outsiders, providing the group with its colloquial name.

1856

In 1856 mayoral election, William Magruder defeated the Know-Nothing candidate, Silas Hill. In a message to the Circuit Court, he labeled “the police department so inefficient, that a citizen has to be murdered in the streets, and the murderer suffered to escape, even after he had been arrested, and other high crimes and misdemeanors have been committed.”

-Alfers, p. 17.

James Baggott replaced Horatio Steele as Chief of Police and Baggott then fired twelve of the police officers who had been appointed by Mayor John Towers. Even more sweeping changes were being made in the Auxiliary Guard as the entire force was fired.

1857

John Mills, a former boot maker, was named Captain of the Guard replacing James Birch. The changes appeared to be effective. For the first six months of 1857, Washington was relatively peaceful. The 1857 inauguration of James Buchanan had attracted the usual number of pickpockets and other criminals to the city, but the regular and special police hired for the inauguration kept the peace and there were relatively few complaints. However, one was an embarrassment as some police officers on duty at the White House apparently were neglecting their duty while thieves made off with some goods.

The final months of 1857 where dangerous times as at least ten policemen were injured in the line of duty. Although the Know-Nothings had been defeated in the 1856 Mayoral election,the 1857 city elections promised to be a brawl. On election day a group of “Plug Uglies” from Baltimore descended on the city to help the local “Chunkers” and “Rip Raps” prevent naturalized citizens from voting. Chief James Baggott and his men, acting on a tip, went to the train station to check on them. They described the “Plugs as rowdies, with hair closely cut,mean looking persons and suspicious.”

-Alfers, p. 17.

With trouble brewing, the city police delivered the ballot boxes to the various precincts. At 9:30 A.M., in the first precinct of the Fourth Ward, the “Plugs”, “Chunkers”, and “Rip Raps” assaulted a line of about one hundred voters, of whom two-thirds of were naturalized citizens. Police Officer B.T. Ward describedthe scene as, “The rocks flew like hail, mixed with pistol balls…. I expected every minute to fall.”

-Alfers, p. 17.

After Chief Baggott and others were reported wounded, and the “impudent disturbers of the peace were thus allowed to range up and down without molestation,” Mayor William Magruder requested President James Bachanan to call out the Marines. About one hundred Marines marched on the rioters. The plugs and their cohorts now armed with a six-pound brass swivel cannon prepared to resist the troops at Northern Liberty Market. They did not use the cannon but retreated at the sight of the Marines, hurling stones and firing revolver shots at the advancing Marines. The Marines returned fire. At least twenty people were wounded andeight people were killed including one bystander.

After weeks of disturbances in the Fall of 1857, including riots by the city firemen, rowdyism and an attempt to stab Captain John Mills of the Auxiliary Guard, the City Council authorized the mayor to appoint twenty-five special police officers at $2.00 per night under the captain of the auxiliary guard. The city spent $2,872 on the special police officers.

Preservingthe peace was an extremely hazardous business during the last two months of 1857. The newspapers described the situation as “a perfect hell.” Ten policemen were injured in the line of duty with injuries ranging in severity from that of the Auxiliary Guardsman, Benjamin Klopfer who was shot in the left eye, to that of Auxiliary Guardsman William Lloyd, who was injured when he was punched in the face while quelling a riot. The STAR summed up the situation as “to charge a body of men, who have been thus maimed and bruised in the discharge if their duty, with cowardice and inefficiency, is ungrateful as well as unjust.”

-Alfers, p. 17.

A grand jury investigated the bloodies riot which the District of Columbia had witnessed concluded that, “In view of all of the circumstances, we declare our opinion that the police force, as at present organized, is not adequate for the purposes intended.”

-Alfers, p. 18.

1858

On January 7, 1858, Mayor William Magruder approved an act to reorganize the police system in Washington. The city was divided into ten police districts. Four officers were authorized for the first, eighth, and tenth districts; two for each of the other districts, and one for the B. and O. depot, who were required to remain on duty until the commencement of the night-watch. The compensation of the officer at the depot was fixed at $390 per annum; that of the others at $630, and they were allowed to receive rewards publicly offered by corporations, States, or the United States.

The same act required a uniform for the force and designated a winter and summer uniform.

The winter uniform shall be as follows: a blue frock coat, with standing collar, and yellow metal buttons blue pantaloons, with a red stripe, half an inch wide down each side and a cloth cap marked in front with the distinguishing number of the officer which shall always be exposed as well as a metallic badge marked “City Police” conspicuously worn. Additionally, a uniform overcoat may be designated by the mayor.

The lieutenants of police shall wear on the front of their caps instead of the number, the letters “L. P.”

The summer uniform shall be as follows: a coat of the same kind as that prescribed for winter, white pantaloons, white vest with yellow metal buttons and a dark (uniform) summer hat with all the distinguishing marks for the cap of the winter uniform. The marshal of police shall wear such uniform and distinguishing badge as the mayor shall prescribe.

In April 1858, Mayor Magruder was authorized to appoint a temporary police force of one hundred men, twenty-one of them to be mounted. A joint committee was also selected to report to Congress “the inability of the corporation to maintain permanently such a police force as is necessary for the preservation of order under existing circumstances,” and to urge the establishment of a permanent force and municipal court.

1861

1860 wasn’t only a turning point in the country’s history, the city of Washington was coming closer to the creation of the Metropolitan Police Department.

The election of Abraham Lincoln led to the secession of seven states in the South before the inauguration and four more when the Civil War began with the Battle of Fort Sumter. Washington was a border town, but it had strong sympathies for the South. Many of the city’s police force began slipping away to the south. Others were dismissed when it became obvious where their loyalties were. The City Council hoped that the government would assume responsibility for maintaining order in the Capitol and in May of 1861, a Provost Guard began patrolling Washington streets at night. Later when the city police force was further reduced, the Provost Guard began patrolling during the day.

A Metropolitan Policing System had for some years been in operation in London, New York, Baltimore, and other large cities. President Abraham Lincoln recognized that the District of Columbia was in desperate need of a regular police force and that it should be free and independent of political influences.

On July 16, 1861, Roscoe Conkling, a Republican member of the House of Representatives from New York introduced a bill as an amendment to an act to establish an auxiliary watch for the protection of public and private property in the city of Washington. The amendment provided that the appointment of the watch or guard should be taken from the mayor and given to the Secretary of the Interior. On the same day the Washington City Police bill, authorizing the President and Speaker of the House to appoint the auxiliary guard, was passed by the Senate.

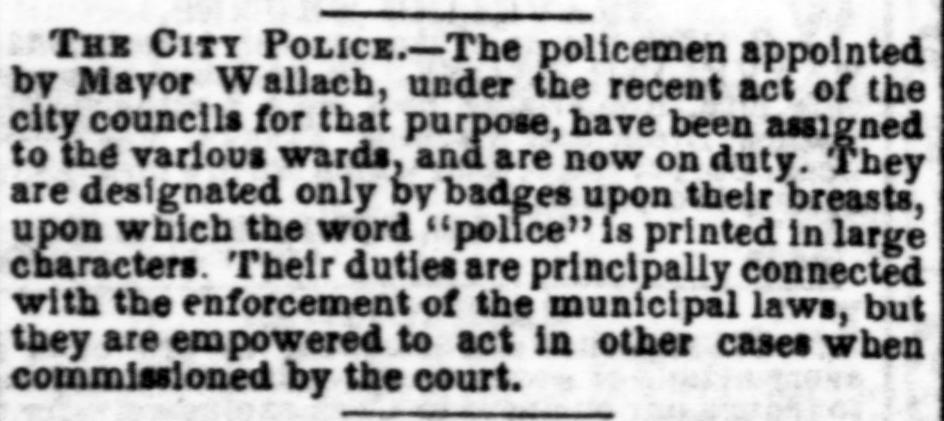

President Lincoln gave his approval and on August 6, 1861, an act merging Washington, the corporation of Georgetown and the County of Washington into the Metropolitan Police District of the District of Columbia was passed. A few days later Zenas C. Robbins, Joseph F. Brown and Richard Wallach were appointed commissioners from the city of Washington: Wm. H. Tenney, from Georgetown, and Sayles J. Bowen, from the county of Washington.

On August 13, 1861, President Lincoln personally requested Zenas C. Robbins, Esq., a member of the newly created Board of Metropolitan Police Commissioners, to take the first railroad train to New York and, upon arrival, to thoroughly familiarize himself with the features of the New York Police System and the experiences of its leadership. The New York Police System had been modeled after the famous Metropolitan Police of London. This latter force was then recognized as the world’s most outstanding police organization. It was based on the results of Mr. Robbins’ study of the New York Police System that the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia was modeled.

On August 19. 1861, the First Meeting of the Police Commissioners was in the aldermen’s chamber of City Hall. Justice John H. administered the oath of office to Johnson to all but Mayor Berret, who declined to take it on the grounds that it was superfluous. Mayor Berret and Messrs. Richard Wallach and Joseph F. Brown, of Washington; Mayor Addison and Mr. William H. Tenney, of Georgetown, and Sayles J. Bowen, of the county, present; Mr. Robbins was absent from the city at that time. Mayor Berret called the meeting to order. Mr. Tenney moved the session to be held with closed doors, which was adopted, and the room was cleared.

The board organized permanently by the election of Richard Wallach as president, J.F. Brown as treasurer, and Thomas A. Lazenby as clerk.

On August 24, 1861, Mr. Berret made a motion that the auxiliary guard continued in service until September 1.

At the August 31st board meeting, the members fixed the standard height of policemen at five feet six inches, agreed upon a sub‐division of the police precincts, and elected fifty‐six patrolmen for Washington. The Auxiliary Guard were notified that their term of office expired on that day, and their last tour of duty ended on Sunday morning, September 1st.

On September 3, 1861, William B. Webb, the first superintendent of the Metropolitan Police Department, was elected, and at the same meeting, it was decided that an ex officio member could not hold an office, with Mr. Wallach, having been in the meantime elected mayor of Washington in place of Mr. Berret, who had been arrested by the military authorities. As a result, Mr. Z.C. Robbins was elected president.

In September 1861, William B. Webb was appointed the first superintendent of police for the District of Columbia. At that time, the authorized strength of this force consisted of a superintendent, 10 sergeants, and enough patrolmen as might be necessary, but not to exceed 150. Up to ten precincts were authorized.

Upon assuming office, Webb began the task of investigating and qualifying applicants for the authorized positions. Although speed was essential, finding good men was equally important. This was not easy because as the Civil War was moving forward, the military was also looking to fill their ranks with able-bodied men.

In 1861, a police applicant had to meet several prerequisites. He had to be a U.S. citizen who was able to read and write the English language, have been a resident of the District of Columbia for 2 years, as well as having never been convicted of a crime. Each applicant also had to be at least 5 feet 6 inches tall and be between the ages of 25 and 45 years old. Those hired were required to be in good health, of a sound mind, and possess good character and an upright reputation. Superintendent Webb made it his policy to interview each candidate personally, working an average of 20 hours a day to fill out the department. Local physicians volunteered to give the required physical examinations to applicants, although they seem to have been perfunctory in nature.

The superintendent of police’s salary was $1,500 annually, with sergeants earning $600 and patrolmen $480 a year.

On September 10, 1861, more officers were sworn in bringing the total to 10 sergeants and 150 privates or patrolmen—with 16 acting as roundsmen (a position now filled by the sergeants.)

On September 11, 1861, the sergeants and most of the personnel for staffing two precincts had qualified for duty and on September 12, 1861, the bond for William B. Webb was approved and he was officially appointed by the Board of Police Commissioners to be the Metropolitan Police Department’s first “Major and Superintendent.” The swearing-in ceremony was performed in the Senate wing of the Capitol Building. The men immediately went to work–or at least half of them did, because the force was divided into two 12-hour tours of duty.

“I’ll never forget the first day we went on duty.” It was raining and the first roll call was at 6 o’clock in the evening. The city was divided into ten precincts. When the force was organized Mr. William B. Webb was chief and there were one hundred and fifty members. There were no station houses, and the roll was called out in the street. I was in the old seventh ward, which was in South Washington, and answered the roll call on the cellar door of the old Island hall.

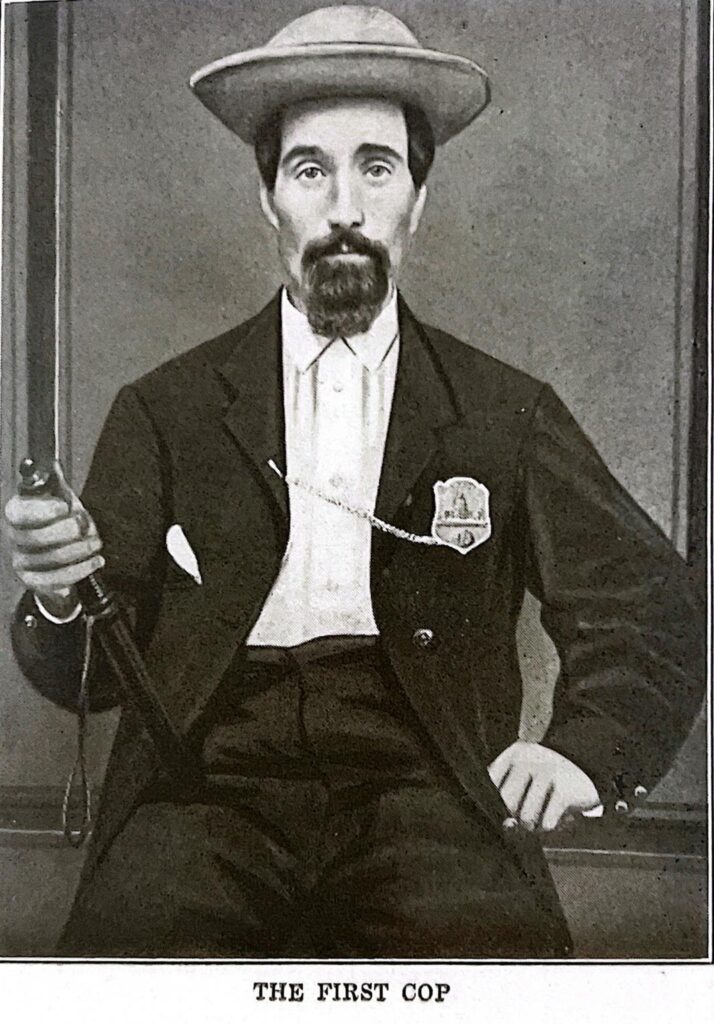

“We were a pretty crowed that evening when we started out. We had no batons, badges, uniforms or clubs, but were provided with a small oil cloth band to put around our hats bearing the inscription: “Metropolitan police.”

Policeman Augustus Brown bears the distinction of being the only man who wore a badge the first day he went on duty. Brown, who was a member of the corporation police prior to the organization of the metropolitan force still had his badge and pinned that to his overcoat.

“The first thing the men did was to go to a pile of wood and get clubs, the regulation size being 22 inches long. Some of the primitive batons were of good size and looked as if they were to be used as mallets father than on the heads of offenders against the laws.” -The Evening Star, March 8, 1890

These tours were from midnight to noon and noon to midnight. The men on the force worked 7 days a week with no days off and no provisions for any vacation. They were issued no equipment. Members were supposed to supply their own handguns and were prohibited from carrying shotguns and rifles. Additionally, they were not allowed to carry canes or umbrellas.

“How about the hats?” inquired the reporter. “Some went on duty wearing slouch hats, others had derbiemand silk hats and some hardly had any hats,” was his reply, “but it was only four months before the government furnished uniforms, caps and clubs, but they don’t furnish them now. The oil cloth, which was the only thing to designate the policemen from other citizens, gave them the appearance of hotel porters and they were often called such by the soldiers. -The Evening Star, March 8, 1890

“The police at that time had the old‐fashioned whistles with a ball in them. They took the place of the rattles that were used by the old corporation police. Even after the change in the force’s rattles were kept in many houses and were used when police assistance was necessary. “The prisoners were tried at the old central guard house, the soldiers arrested being turned over to the military court, which occupied a portion of the building. The punishment meted out to the offenders was about the same as now, in petty cases the fine usually being $5 and costs. The costs were either 48, 54 or 94 cents, according to the circumstances attending the case. The jail building was at the corner of 4th and G streets, where the pension office now is, and persons sentenced to that prison were escorted there by an officer and compelled to work. The workhouse was situated where the alms house now is and $1 was allowed by the magistrate for transporting prisoners there. The officers then used to hire a hack or other public vehicle and go to the prison in style. Sometimes there would be a dozen or more prisoners to be taken at once and then an omnibus was procured. -The Evening Star, March 8, 1890

The newly formed police force did not have any insignia to display for their authority, Webb’s first act was to procure temporary badges for the Metropolitan Police Department. In doing so, Major and Superintendent Webb was given a budget of twenty dollars to provide a badge for 9 Sergeants and 110 patrolmen and those numbers were climbing as more men were added to the rolls.

Henry Polkinhorn was given the contract to print the first badges for the Metropolitan Police Department at a cost of fifteen dollars.

The uniforms adopted in the early days were not as gorgeous as those that have since taken their place. The Superintendent wore a frock coat with police- buttons, the sergeants, double-breasted frock coats and blue pants, while the patrolmen were attired in navy-blue coats with rolling collars and nine buttons, two fastened at the hips and two on the skirt, blue waistcoats, and pants with white cords down the seams. The coats were to be always buttoned when officers were on duty, and hats were the official headgear for all members of the force.

January 29, 1862, Evening Star

On September 23, 1861, the Capitol building of the United States was selected as the emphasis for the patrolmen’s badge. The Superintendent’s badge was adorned with a shield of gilt or gold, surmounted with an eagle, while for the Sergeant’s badge was chosen to be a silver plate with an eagle and a number.

Lamb Seal & Stencil Co. supplied the badges and after 1895 by the Bastian Brothers Company of Rochester, New York.