The goal of collecting badges is to obtain an authentic department issued, officer-worn badge. With the Metropolitan Police Department, there isn’t always an accurate test to know if what you are looking at was a departmental issued badge or whether it is a copy produced by any number of companies, a secondary badge from the stamping company or a novelty knock off.

Most of the officer badges of the Metropolitan Police Department were not Hallmarked. At times Lamb Seal & Stencil Company, Inc. would hold the contract however they may have sourced out part of the order to another company like Blackinton. Additionally, companies like Northeast Emblem and Badge, and Blackinton would not only provide badges to the Metropolitan Police Department, they would also sell badges to the FOP or other outlets where second and novelty badges could be purchased.

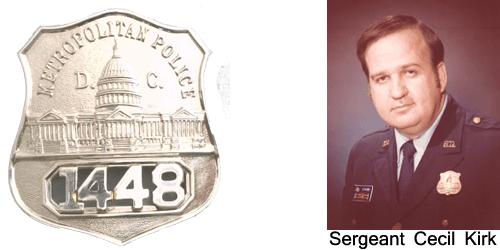

So, what is an authentic badge? If an officer was issued a Blackinton badge with no hallmark but wore an FOP purchased Northeast badge, which badge would the collector find more desirable? The departmental issued Blackinton badge which stayed in the sock drawer or an officer’s second Northeast badge, which was not authorized but was carried for the bulk of the officer’s career? Chances are those badges looked exactly alike and a collector looking at them five, ten or fifteen years later may not see any real difference.

On September 11, 1861, the first installment of men for the Metropolitan Police Department were qualified and on September 12, 1861, the bond for William B. Webb was approved and he was officially appointed by the Board of Police Commissioners to be the Metropolitan Police Department’s first “Major and Superintendent.”

The newly formed police force not having any insignia to display for their authority, Webb’s first act was to procure temporary badges for the Metropolitan Police Department. In doing so, Major and Superintendent Webb was given a budget of twenty dollars to provide a badge for 9 Sergeants and 110 patrolmen and those numbers were climbing as more men were added to the rolls.

Henry Polkinhorn was given the contract to print the first badges for the Metropolitan Police Department at a cost of fifteen dollars.

Henry Polkinhorn was born in 1813 in Baltimore, Maryland. His father, Henry, Sr., was an English immigrant who was a saddler by trade and ran a successful saddle company. As a saddler in Baltimore, Henry Sr. was successful but instead of staying with the family business, Henry Polkinhorn, Jr moved to Washington, D.C. and married Marianne Brown in 1839. Henry became a printer and Marianne and he had six children together. Marianne died in 1857 and Henry married Rachel Ann Barnes less than two years later. Henry Polkinhorn was extremely successful as a printer and a few years after starting his print shop, he built his own building at 634 D Street, N.W. where he printed the first badges for the Metropolitan Police Department.

Henry Polkinhorn from the Harvard Theatre Collection

Henry Polkinhorn was given the contract to print the first badges for the Metropolitan Police Department at a cost of fifteen dollars.

Henry Polkinhorn was born in 1813 in Baltimore, Maryland. His father, Henry, Sr., was an English immigrant who was a saddler by trade and ran a successful saddle company. As a saddler in Baltimore, Henry Sr. was successful but instead of staying with the family business, Henry Polkinhorn, Jr moved to Washington, D.C. and married Marianne Brown in 1839. Henry became a printer and Marianne and he had six children together. Marianne died in 1857 and Henry married Rachel Ann Barnes less than two years later. Henry Polkinhorn was extremely successful as a printer and a few years after starting his print shop, he built his own building at 634 D Street, N.W. where he printed the first badges for the Metropolitan Police Department.

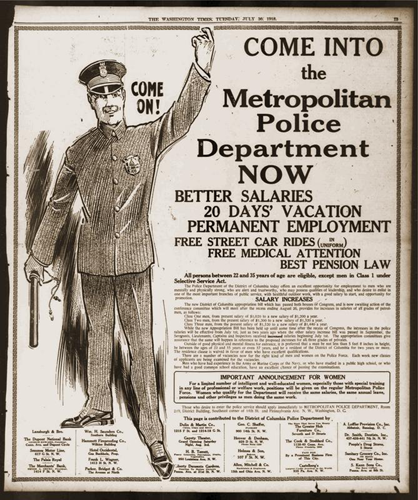

The uniforms adopted in the early days were not as gorgeous as those that have since taken their place. The Superintendent wore a frock-coat with police- buttons, the sergeants double-breasted frock-coats, and blue pants, while the patrolmen were attired in navy-blue coats with rolling collars and nine buttons, two fastened at the hips and two on the skirt, blue waistcoats, and pants with white cords down the seams. The coats were to be buttoned at all times when officers were on duty, and hats were the official headgear for all members of the force.

The blue arrow on the map points to 634 D Street, N.W. in 1861.

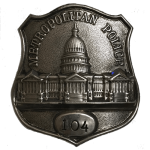

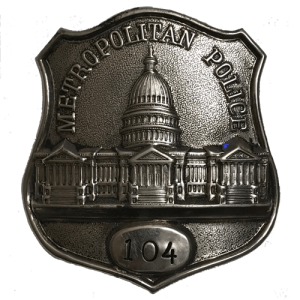

On September 23, 1861, the Capitol building of the United States was selected as the emphasis for the patrolmen’s badge. The Superintendent’s badge was adorned with a shield of gilt or gold, surmounted with an eagle, while for the Sergeant’s badge was chosen to be a silver plate with an eagle and a number.

The badges were supplied by Lamb Seal & Stencil Co. and after 1895 by the Bastian Brothers Company of Rochester, New York.

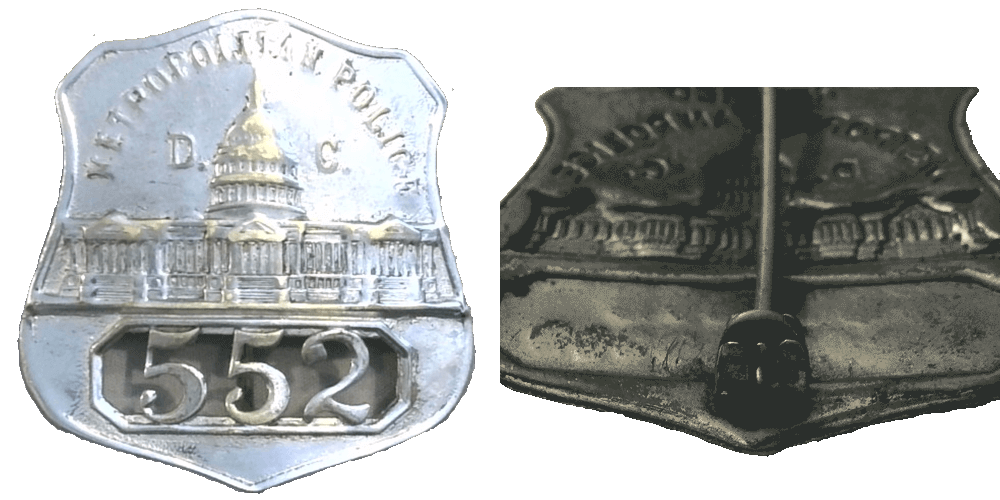

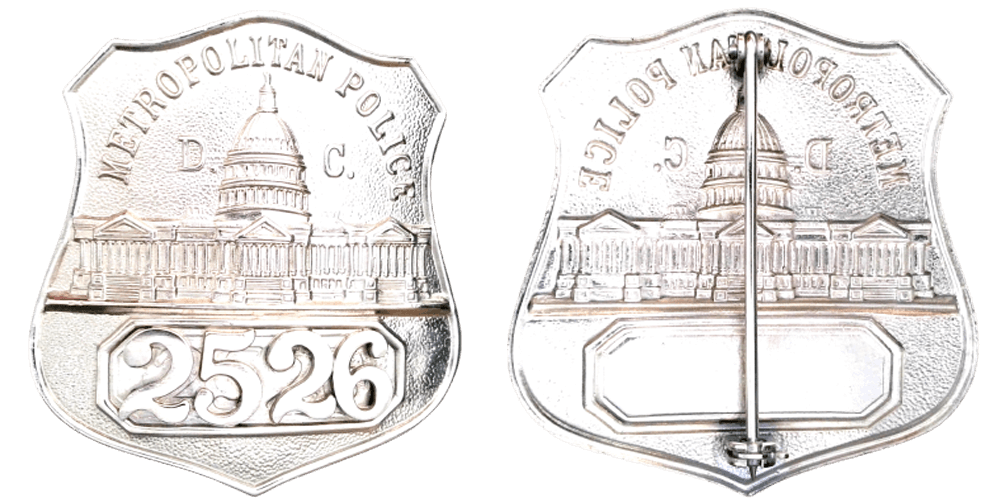

As the department moved into the 1900s, the officer badges moved away from an engraved or stamped number in the oval and the department went to applied numbers. Starting in 1904, a revision of the badge was undertaken not only for officers but officials as well [the Rank of Sergeant and above]. The officer badges were a shell back with applied numbers to the front of the badge. The letters “D” and “C” were added to the sides of the Capitol dome. Blackinton, Northeast, and Bastian Brothers became the major suppliers of badges to the department.

In 1919, only the letters “D” and “C” were applied next to the Capitol building. Beginning in 1920, a period was applied to the rear of the “D” and “C” initials.

Prior to 1926, members of the Metropolitan Police Department had to purchase their uniforms at their own expense. This had led to wide variations in what was a uniform. In 1915, nine different styles of caps were worn by members of the department. In 1924, a request was made for a change in uniform coat changing from a stiff standing collar to the lapel or roll collar type.

Around 1918, a short-lived badge style cap plate was introduced for the force. That cap plate lasted for approximately 10 years until it was replaced by the current style of cap plate.

As the years went on, these badges were often referred to as having punch out numbers. The rumor being that if an officer was engaged in an activity they may not wish to be identified, they could simply punch out one of the numbers on the badge so that anyone writing down the badge numbers would have the wrong person.

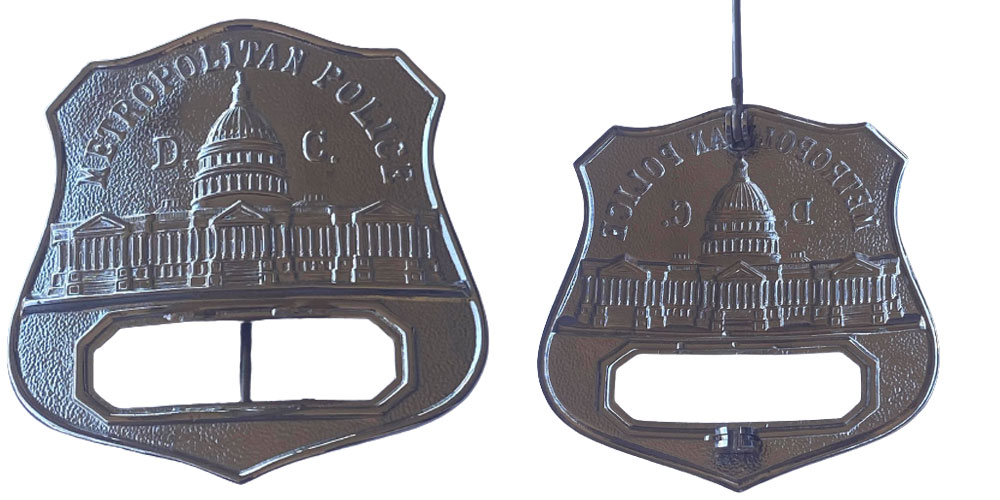

In 1999, the department began adding plates with stamped numbers where the applied numbers would be, which sometimes was called, ‘closing the window.’ This saved a lot of repairs to the applied number badges. What it did was create a police force with a grab bag of styles and badge numbers. Even those with applied numbers would find that over the year’s fonts had changed and their badge number may be applied with digits in different fonts. The department began to remedy that. On October 1, 2005, the department discontinued the use of the applied numbers or “punch-out” style badges meaning that they no longer carried any police powers. Officers who had those badges were instructed to report to property and that they would be issued a Temporary badge with a T number.

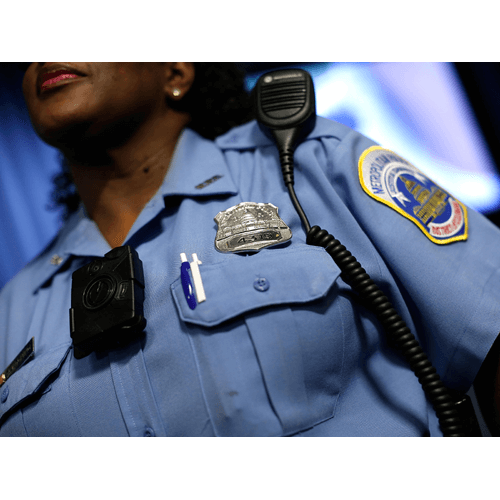

In November 2005, the department revamped its badge system. Blackinton was chosen as the official provider of department badges. These changes included going to a solid back badge as well as:

*Creating a new block numbering system for all badges and cap plates by rank from the Chief of Police down through Officers to include reserves, cadets and crossing guards.

*Placement of badge numbers on the front of all badges with rank labels for officials on the front of all badges.

*Creation of a serial number tracking system and the placement of the serial number on the back of all badges.

What before was guesswork of trying to determine issued badge from other has now turned into a relatively simple exercise. After examining the front and rear of a badge it is readily obvious whether the badge is a Blackinton departmental issued badge or not.