On August 6, 1861, the Thirty-Seventh Congress of the United States created a Metropolitan Police District of the District of Columbia or what became known as the Metropolitan Police Department, District of Columbia, MPDC. Buried within that Act is Section 12 of Chapter 62 which described the duties of special patrolmen:

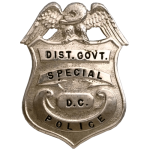

“And be it further enacted, That the board of police may also, men powers and upon any emergency of riot, pestilence, invasion, insurrection, or during any day of public election, ceremony or celebration, appoint as many special patrolmen, without pay, from among the citizens as it may deem advisable, and for a specified time, and during the term of service of such special patrolmen, he shall possess all the powers and privileges, and perform all the duties of the patrolmen of the standing police force of the District. And such special patrol shall wear an emblem, to be presented by the police commissioners.”

Although the Metropolitan Police force may have been new to the District of Columbia, Special Policemen were not. During this time and many years moving forward, the terms Night Watchman, Watchmen, Additional Private, and Special Police were used interchangeably. The use of Special Police may have been just a minor footnote in private security in the District of Columbia except for two very important factors. 1) The District of Columbia is the seat of the Federal Government. With all of the different Federal buildings, agencies and departments, Washington experienced more governmental authorized protection than other larger cities whose Special Police officers guarded corporations. 2) Presidential Inaugurations. The Inauguration of the President of the United States swelled the size of the city every four years which resulted in the use of Special Police not only from the local citizenry but from police forces across the country. Again because of the federal involvement of an Inauguration this took on a unique experience and these unique experiences.

In February 1849, the assault of “two respectable and unoffending citizens” caused the City Councils [Washington and Georgetown] to appropriate money for a Special Police force which was organized under the “superintendence and control of the Captain of the Auxiliary Guard.” Those Special Policemen remained on duty through the inaugurations of William Henry Harrison on March 1849 and also Zachary Taylor in April of 1849.

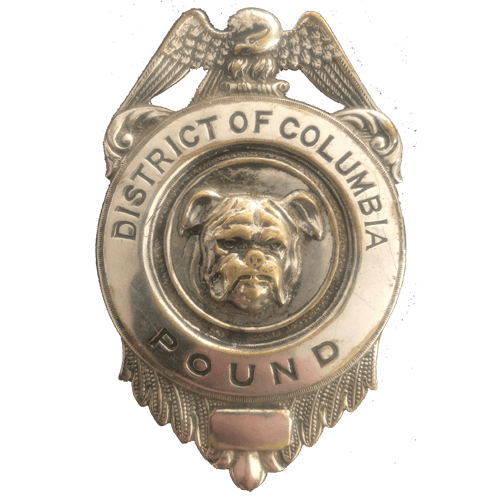

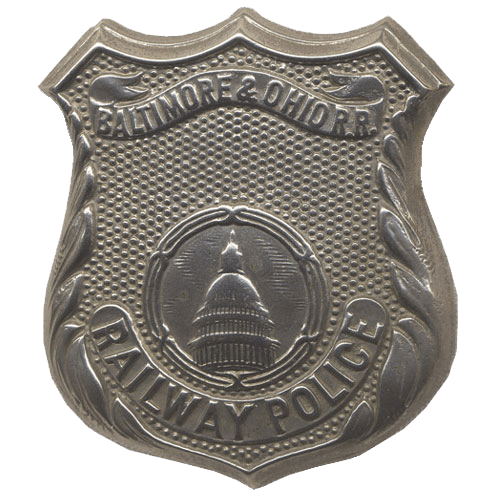

An Act of Congress in 1852 authorized a watchman to be employed at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad [B&O] depot, located at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 2nd Street, NW, which at that time was the only railway station within the District of Columbia.

For the Inauguration of President Franklin Pierce on March 4, 1853, the Mayor, John W. Maury, was empowered by Congress to employ as many Special Officers as he deemed necessary at a cost of $1.50 per day. Fifteen men were selected for night work and seven men were selected for day work. All of the men were to report to the “Office of Chief of Police” to receive their commissions.

Later in April 1853, Mayor Maury was authorized to employ two extra men in each ward of the city for the suppression of “incendiarism.” [Arson]

In 1857, F.A. Klopfer, the Chief of Police, oversaw the 15 men of the Auxiliary Guard however the citizens began to complain that the amount of crime at night had become greater than the police force could handle, so the City Councils authorized the mayor to appoint twenty-five Special Police Officers at the rate of $2.00 per night. The Special Officers would operate under the direction of the Captain of the Auxiliary Guard and that each of the Special Officers would wear a badge on the collar or lapel of their coat which would be visible to everyone who meets them. The District ended up spending $2,872 for these Special Police Officers.

In April 1858, the City Councils authorized the mayor to appoint a temporary police force of 100 men, 21 of which were to be mounted to assist with the preservation of order.

For the elections of June 7, 1858, Mayor William Beans Magruder was expecting trouble at the polls and disbursed Special Policemen to every polling place. Commissions and badges were furnished to each member of the Special Police and the law also allowed the Special Police officers to be armed “both for their own protection and to enforce obedience.” In previous elections, the polls were not as closely guarded and mobs would discourage people from voting.

Everything had been fairly calm in the 4th Ward until around 2:00 P.M., when in the back of City Hall, which at the time was located near Fourth and E Streets, NW, Special Police Officer, A.R. Allen attempted to disburse a noisy crowd which had gathered. While attempting to disburse the crowd, Officer Allen arrested one of the ring leaders and was struck in the back of the head with a brick, letting the prisoner escape.

Officer Allen drew his revolver and was again knocked to the ground. Officer Allen fired four times into the crowd killing an Irishman. The crowd then became a mob and chased Officer Allen back to City Hall, shooting at him as well as throwing rocks and bricks at him until he was to shut the doors to City Hall. The Mob then began shooting into city hall.

The U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia, William Selden had also taken the precaution. He had assembled a posse made up of 100 Deputized mounted men who would go back and forth to the various polling stations. Upon hearing of the trouble at City Hall, Marshal Selden and his posse rode to City Hall and disbursed the crowd. Three individuals were shot in the melee before order could be restored.

It was becoming obvious that the current policing model for Washington, Georgetown and the other areas of the District of Columbia wasn’t working. Another Police Act was passed December 30, 1859, which included a supplemental Act authorizing an addition to the force of not more than forty men at $50 per month. These Special Policemen were appointed under the Captain of the Auxiliary Guard.

With the creation of the Metropolitan Police, under the provision for the appointment of Special Policemen, W. S. Kneas was the first person commissioned as a Special Policeman at the Willard’s Hotel. The newspapers mentioned Kneas more than a few times for arresting criminals.

James Etter, a doorkeeper, and watchman for the War Department told a reporter from the Chicago Tribune the story of why he will never abandon his post.

Etter explained his story by saying that “One day during the war (Civil War) I was sitting here when a tall, angular gentleman entered the main door and asked if the Secretary [Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton] was in. I told him that it was too early for the Secretary to be in his office.”

“At what hour can I depend on finding him here?” he asked. “I told him and with a pleasant ‘Thank you’ he walked away.”

“Promptly on the hour the tall gentleman ascended the steps, walked in the door, and I was almost struck dumb when he asked me if I would not go into the Secretary’s room and tell him to step out in the hall. I recovered myself and informed the caller I could not leave my post of duty, and even if I could I did not think the Secretary would come out to see him.”

“He replied: ‘Oh, I guess he will, and as for leaving your post, I will be personally responsible for that. I am Mr. Lincoln, and I will simply take your badge and keep door while you step in for me.’”

“Well, I couldn’t doubt him and he pulled off my badge, pinned it on his coat and took my chair, just like an old-time watchman.”

“A smile played over his face as I left him, and you can rest assured it was not long before he and the Secretary were holding a quiet talk in an out-of-the-way corner in the hall.”

In 1866, The National Republican newspaper began listing Additional Privates receiving 90-day Commissions.

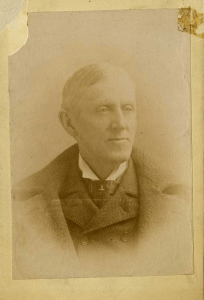

John E. Buckingham

In May 1876, John E. Buckingham received a police commission as a Special Policeman at the National Theatre. While during research on the Lincoln assassination an individual found a note on the back of a photograph of John E. Buckingham written by Cordelia Jackson on May 6, 1914. The inscription reads:

‘Mr. John E. Buckingham, the —* doorkeeper at Ford’s Theatre in April 1865. Mr. Buckingham was the last person to whom Booth spoke before shooting the President. “What time is it,” asked Booth as he entered the theater. “Look at the clock and you will see,” replied Mr. Buckingham. From an interview with Mr. Buckingham, Jan. 1900.’

On March 4, 1877, for the inauguration of Rutherford B. Hayes, one hundred Special Policemen were employed to preserve public order.

In 1881, when President Garfield was assassinated at the Baltimore & Potomac Railway station, it was Metropolitan Police Officer Kearney and Special Police Officer Parks who was assigned to the railway station who captured the assassin, Charles Julius Guiteau.

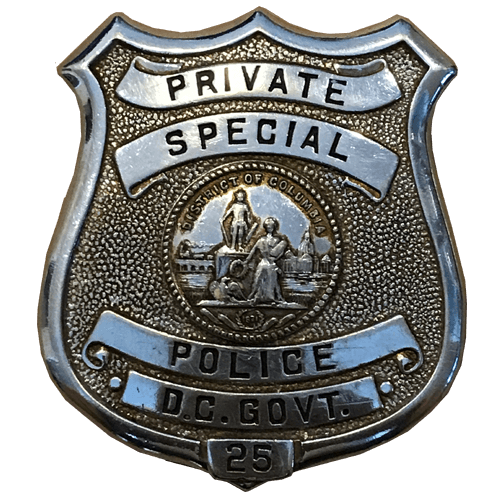

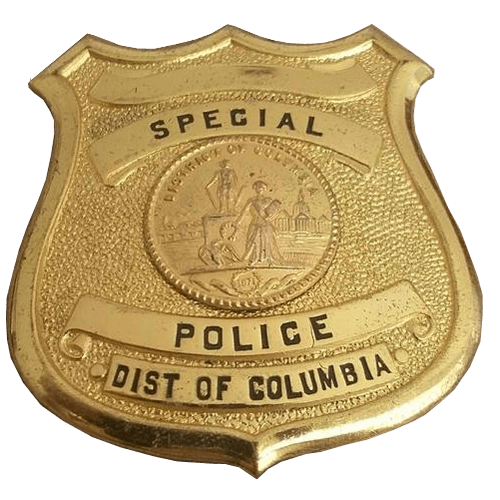

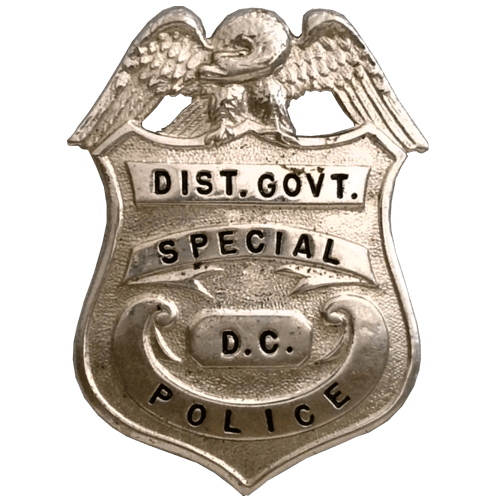

For the March 4, 1885 inauguration of Grover Cleveland, the District Commissioners contracted with Mr. Julius Baumgarten to produce 300 Special Police badges, “like those now used by our police force.”

For the 1889 Inauguration, Major William Moore when speaking to a reporter from The Evening Star said that the “proposition of borrowing policemen from other cities for” the inauguration “was absurd. Instead, the Metropolitan Police Department would employ 400 Special Policemen as well as pay the expenses of a number of detectives from New York, Philadelphia, Cincinnati and other large cities.

In early October 1889, the courts required Special Policemen not to carry firearms except when they were on duty.

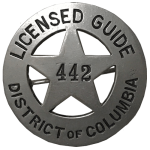

Early on when I started collecting an old-time collector whose name and identity, I have long ago forgotten told me that the first Special Police badge was a five-point cut-out star.

Street Railway Crossing Officers

The Evening Star reported that in September 1895, a new badge was adopted for the additional members of the police force. “It consists of a small star within a circle, the rim of the circle having upon it the words: ‘Additional Private Metropolitan Police.’ The letters ‘D.C.’ appear in the center of the star.”

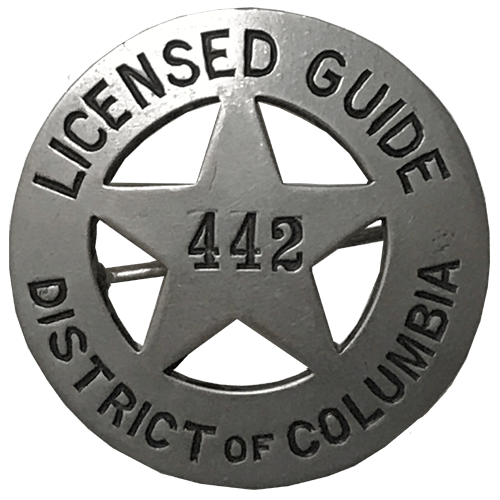

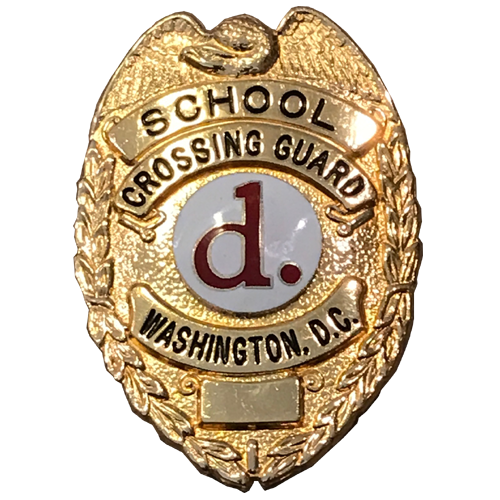

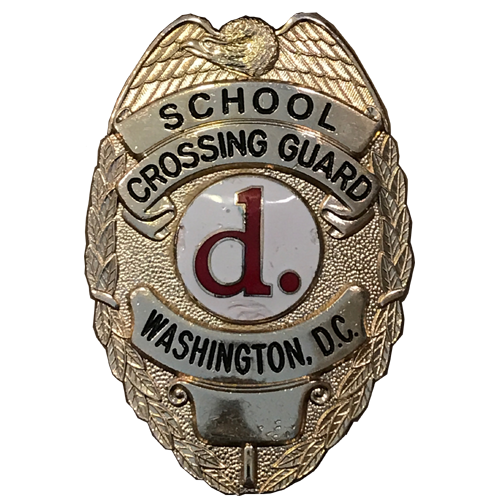

In 1896 as motorized traffic became more widespread, citizens began petitioning the District Commissioners for more traffic enforcement. This included the idea “that a number of wheelmen, preferably members of the League of American Wheelmen, be appointed Special Police without pay, supplied with a badge and power to assist the police in enforcing the regulation governing the streets.”

For the 55th Congress, the Act of Special Policemen was passed on March 3, 1899, on which the current laws (D.C. Official Code §4-114) (1981) or R.S.D.C. No. 378 and 379, June 11, 1878 (D.C. Official Code § 4-130) (1981) outline the qualifications and duties of Special Police Officers in the District of Columbia.

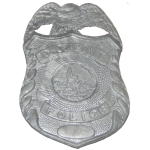

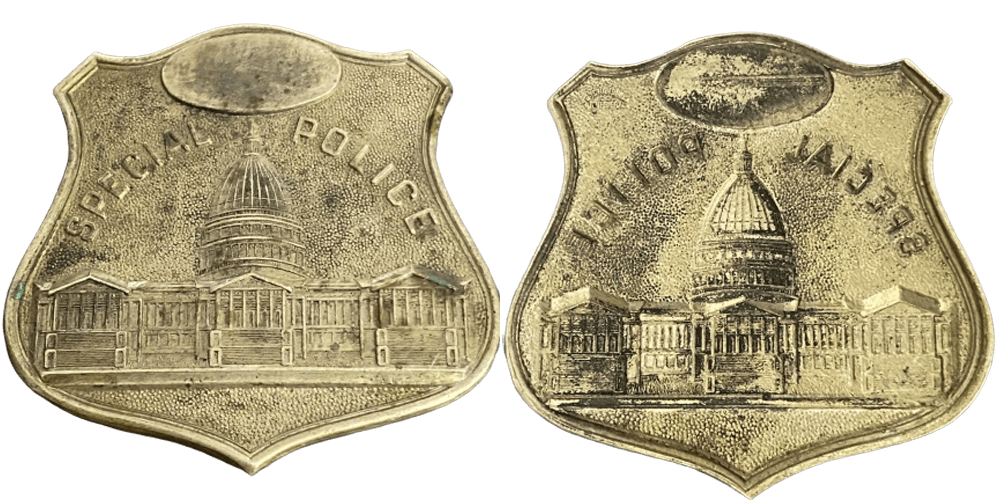

In December of 1908, Major Richard Sylvester furnished the night watchmen with a new badge. According to The Evening Star, “In design it is the same as those worn by the metropolitan police, the distinguishing mark being the words “Special Officer” on either side of the bas-relief representation of the Capitol building.”

The question in historical circles as well as with collecting often is, what did the original look like? According to the 1861 Act which created the Metropolitan Police Department and allowed for Special Patrol; “and such special patrol shall wear an emblem, to be presented by the police commissioners.” As organizations begin often one of the last things which is done is record the decisions or in this case the equipment as historical items.

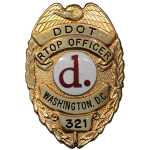

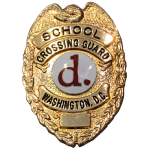

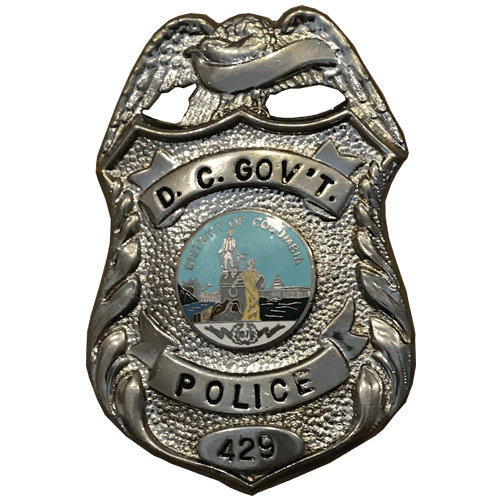

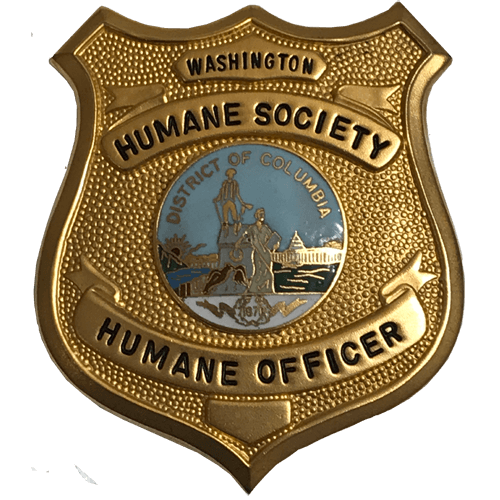

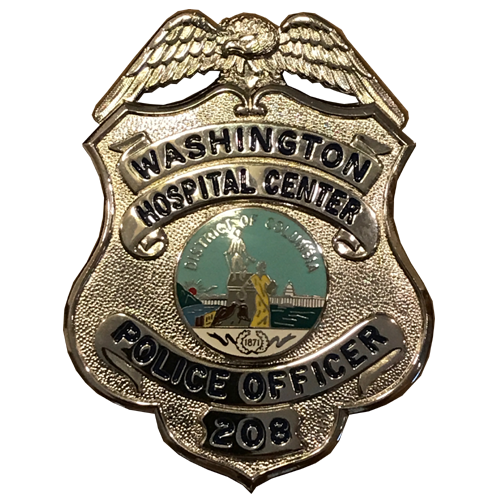

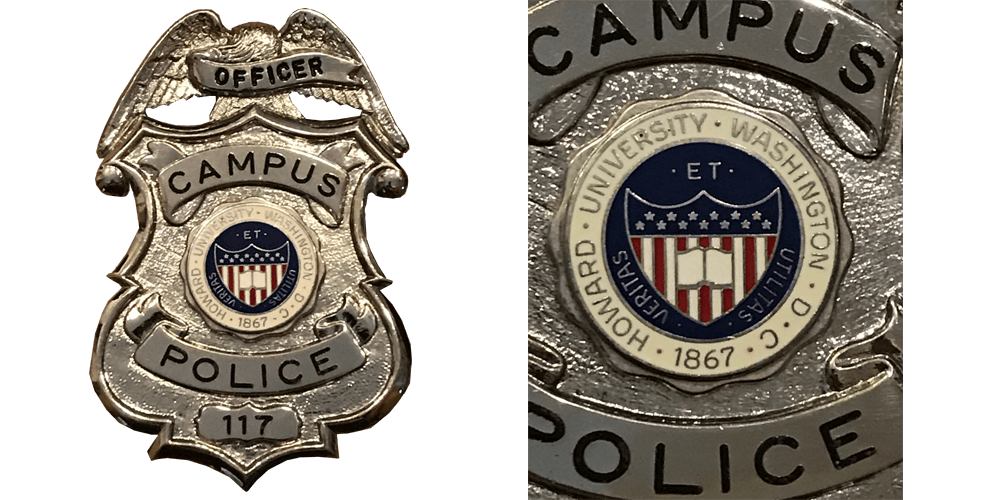

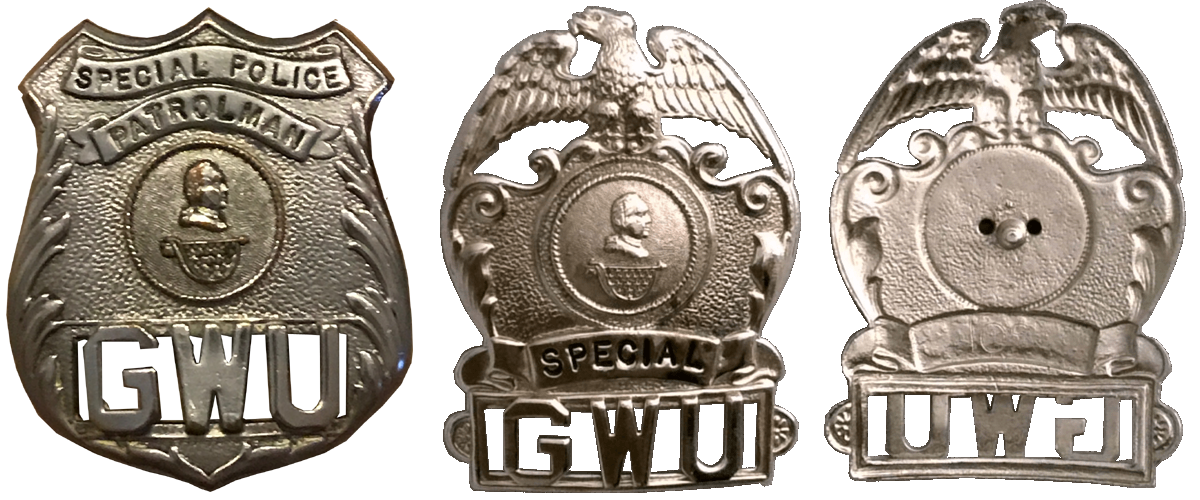

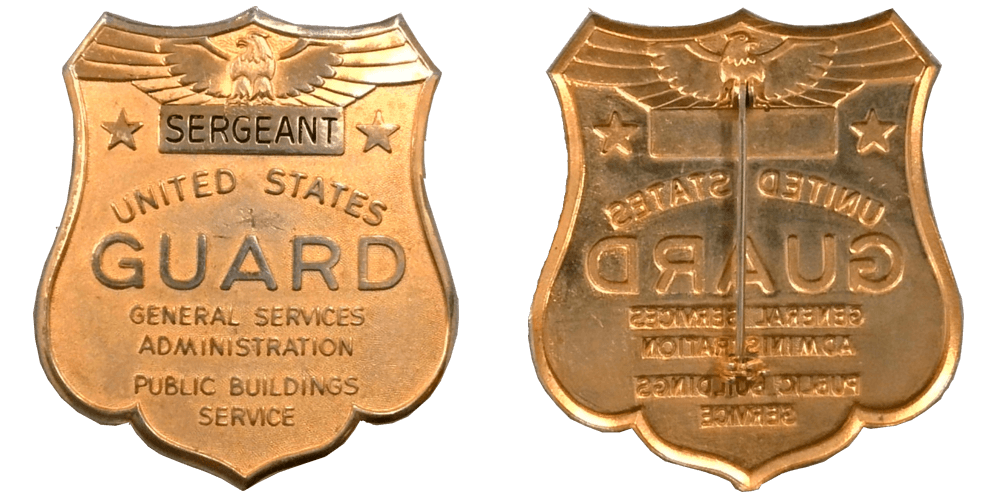

As the years went by those with Special Police Commissions fell into a wide range of areas from Federal Government personnel, to private companies, to District Universities and properties. With Home Rule in 1973, these were eventually codified. There are different types of Special Appointments authorized by DC Law; such as the National Guard during Inaugurations and other Special Events; University Police and DC Government; however private security companies are all appointed under DCMR 6a Chapter 11 and are specifically relegated to private property only.

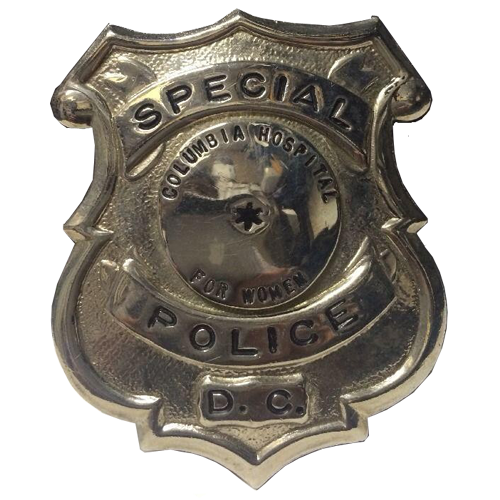

Up until 1983, the Metropolitan Police Department would issue the Special Police Officer badges, which were mostly a Bastion Brothers badge. After 1983, Special Police Officers could officially purchase their badges from a variety of outlets and many companies began producing the badge.

On January 2, 2014, the processing of all license applications, including license renewals, for private detectives, private investigators, special police officers, and security officers was transferred from the Metropolitan Police Department, Security Officers Management Branch (SOMB) to the Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs (DCRA).

SOMB still conducts the initial background investigations and any use of force investigations for SPO’s but DCRA is in charge of the regulation part, and you are seeing many SPO companies looking more and more like police departments. Car designs and badges are completely unregulated in DCMR so the hobby will probably see more and more Special Police badges mimic current law enforcement badges.

Special Police Officers, armed with Colt .45 holstered pistols from the Bureau of Treasury in June 1929 moving money. The “Foreman of the Guard” as identified by his cap plate is wearing the Special Police Officers badge. The badge is also visible on another officers coat.

This photo was originally taken by the National Photo Company in black and white, the picture recently received a digital color makeover by redditor kibblenbits, also known as Patty Allison.

This 1922 picture shows Special Police Officer Bill Norton enforcing the dress code, which mandated that bathing suits should not be shorter than six inches from the knee, along the Tidal Basin Beach of the Potomac River.

The Tidal Basin Bathing Beach was a manmade bank of sand funded by Congress and opened in August 1918 right where the Jefferson Memorial beach is. With swimming lessons and high dives, the Tidal Basin Beach was a relaxing way to beat the D.C. summers even if today, no one would dream of swimming in that water. The Tidal Basin Beach was a segregated beach even though a 16-year-old African-American boy had rescued a 60-year-old white man from drowning there.

The segregation policy eventually helped lead to the beach’s undoing. Congress was set to fund a separate beach in D.C. for African-Americans, but a group of Southern senators torpedoed the effort before plans were finalized. Instead of integrating the Tidal Basin Bathing Beach and providing a recreation space for all, lawmakers had the property dismantled in 1925.